Big news in the archaeology world: In 2003, torrential rains exposed the mouth of a previously unknown tunnel near the Temple of the Feathered Serpent at Teotihuacan, in central Mexico. Feathered Serpent excavation

Now, more than a decade later, researchers have reached the end of the 340’ (103m) tunnel (illustration) that runs about 60’ below the Temple. Finds from the tunnel (including the figure shown in the photo above) include engraved conch shells, amber fragments, mirrors, greenstone statues, ear spools, seeds, worked stone, beads, bones of animals and humans, mysterious clay spheres coated with a yellow mineral – over 50,000 pieces in all.

The photo (left) shows the outside of the structure. A section added around 400 AD obscures the original façade (photo) featuring the feathered serpents that gave the structure its name. Archaeologists debate the significance of the figures. One set seems to be a realistic serpent while the other is a more blocky stylized creature sometimes identified at Tall, the storm god. However, Karl Taube, Mary Ellen Miller, and Michael Coe have said it is more likely a “war serpent” or “fire serpent.” At one time, the circles were filled with obsidian pieces that would have caught the sunlight.

The photo (left) shows the outside of the structure. A section added around 400 AD obscures the original façade (photo) featuring the feathered serpents that gave the structure its name. Archaeologists debate the significance of the figures. One set seems to be a realistic serpent while the other is a more blocky stylized creature sometimes identified at Tall, the storm god. However, Karl Taube, Mary Ellen Miller, and Michael Coe have said it is more likely a “war serpent” or “fire serpent.” At one time, the circles were filled with obsidian pieces that would have caught the sunlight.

<Teo feathered serpent Teotihuacan Facade_of_the_Temple_of_the_Feathered_Serpent

Many people label the new finds in the tunnel under the temple extravagant, gruesome, mysterious. Yet, when viewed next to

earlier finds from Teotihuacan and those of other cities in the area, the new discoveries seem very consistent. It’s their purpose that remains a mystery.

Where and What is Teotihuacan?

Teotihuacan, Maya, Olmec, Mixtec. – The site is located about 30 miles (50 km) northeast of Mexico City.

Teotihuacan is a world-famous archaeological site north of Mexico City, known for its massive pyramids, its precise layout, and the mystery surrounding its birth, its death, and a lot of what happened in between. We don’t know exactly who started this city around 150 BC, why these people embarked on an almost constant monumental building effort from 150 BC to around 250 AD, or what led to the sacking and burning of the city around 550 AD.

Teotihuacan is a world-famous archaeological site north of Mexico City, known for its massive pyramids, its precise layout, and the mystery surrounding its birth, its death, and a lot of what happened in between. We don’t know exactly who started this city around 150 BC, why these people embarked on an almost constant monumental building effort from 150 BC to around 250 AD, or what led to the sacking and burning of the city around 550 AD.

<Teotihuacan View_from_Pyramide_de_la_luna

Adding to the mystery is the lack of any written records. Either the people who burned the city also burned any written materials, or there simply weren’t any. It’s hard to imagine people designing and building such precise, massive structures without a written record, but none have appeared so far in the excavations.

At its height, the city center covered 19 square miles (32 square kilometers) and served a population of 25,000 to 150,000, depending on what source you read, making it the largest city in the Western Hemisphere at the time. Its military power and cultural influence spread throughout central Mexico, out into the Yucatan Peninsula and down into Guatemala.

On the other hand, Teotihuacan also borrowed from earlier and contemporary cultures in Mexico, especially the Olmec, Maya, and Mixtec. The very deliberate, celestially aligned design of earlier Olmec cities like La Venta and Tres Zapotes, with clusters of mounds and central plazas, found its greatest expression in Teotihuacan.

Olmec masks like the one in the photo (left) provided inspiration for the artisans of Teotihuacan. The one shown in the photo (right) came from the newly excavated tunnel under the Temple of the Feathered Serpent. Teotihuacan mask Olmec greenstone masks and figures were a few of many cultural features absorbed into the Teotihuacan culture.

Maya and Mixtec cosmology from contemporary cities also found its way into Teotihuacan culture, as did the value placed on items like fine ceramics and greenstone.

But whatever earlier cities contributed to Teotihuacan, the Teotihuacanos exaggerated. Pyramids became gigantic. The Pyramid of the Sun, (photo, below) the most massive building on the site, stands 233.6’ (71.2 m) tall, and 733.2’ (223.5 m) long and wide, a huge, commanding construction even today. With its decorative plaster coating and top-most temple long gone, it now has the severe look of a multi-national corporate headquarters, a symbol of complete, collective, threatening, and unemotional power.

The whole site was so impressive to the Aztecs who moved into the area 600 years after Teotihuacan was abandoned that they considered it a holy place, a place where gods walked. Even the Spanish conquistadors didn’t destroy it. Its major damage has come from looters, both private and institutional, and from the ravages of time.

Murals painted in upper class Teotihuacan living areas have provided important clues about the people’s spiritual beliefs, especially veneration of a figure often called the Great Goddess, who is associated with the sacred mountain visible from the site, called Cerro Gordo (Fat Mountain), as well as water flowing from the mountain, rivers and rain, fertility and new growth.

<Teotihuacan-Great_Goddess

In the mural shown, the central figure (and the only one shown in the frontal view reserved for deities) has a bird face/mask with a strange mouth that might represent an owl or a spider. Out of the green feather headdress a twisting plant grows – perhaps a hallucinogenic morning glory vine. Circles (sometimes interpreted as mirrors), spiders and butterflies decorate the vine. Flowers sprout from its tips. Birds appear, some with sound scrolls, which probably indicate songs. From the figure’s outstretched hands, drops of water fall. Her torso splits into curling rolls filled with flowers and plants. From the bottom, under an arch of stars, seeds fall toward the border, which is a series of waves carrying stars and underwater creatures.

The figures shown in profile on the right and left of the Great Goddess carry what look like medicine bundles/offerings in one hand. From their other hand water emerges, as well as a cascade of seeds and circles. The entire background is a deep blood red. Karl Taube has related the circles to mirrors that appear in the creation story in which the sun shoots an arrow into the house of mirrors. The serpent, then released, fertilizes the earth. Thus, he argues, the serpent appears on the façade of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent surrounded by a headdress of mirrors.

<Teotihuacan Tepantitla_Mountain_Stream_mura

<Teotihuacan Tepantitla_Mountain_Stream_mura

The panel below the picture of the Great Goddess shows bands of water emerging from a mountain around which red, blue, and yellow human figures swim, interact (sing? dance?) and float among butterflies while plants sprout along a snake-like band of water. Interestingly, for a city known for its militarism and bloody sacrifices, the scene looks idyllic.

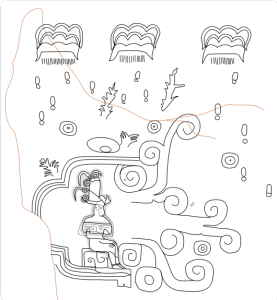

Some experts suggest that the Great Goddess figure was borrowed from the earlier Olmec figure recorded in a petroglyph at Chalcatzingo that shows a woman seated in a cave from which water flows. Outside the cave, maize plants sprout as male rain falls. (Photo, left; illustration, right)

<Chalcatzingo petroglyph Chalcatzingo_Monument drawing

<Chalcatzingo petroglyph Chalcatzingo_Monument drawing

Others point to the Maya water deity Ixchel, the goddess of the moon, rain, surface  waters, weaving and childbirth, sometimes called the Midwife of Creation. (shown as a young woman in the illustration below).

waters, weaving and childbirth, sometimes called the Midwife of Creation. (shown as a young woman in the illustration below).

Maya Ixchel Maiden

In her role as Mother Goddess and weaver, she set the universe in motion through the movement of her drop spindle. She was also called the Spider’s Web because she caught the morning dew in her web and made the drops into stars. However, she had two sides: the young woman and the old crone. She was both healer and destroyer, bringing about the destruction of the third creation through a terrible flood and then helping to birth the new age.

Of course, all of these interpretations have their detractors. Karl Taube interprets the entire site as an exaltation of sacred war. He says the circles found in the caches are related to the mirrors worn by warriors as well as to the house of mirrors from which the creator serpent originated in the creation story. The bodies found in the offertory caches might be captive warriors. His theory, however, doesn’t explain the significance of the murals.

Of course, all of these interpretations have their detractors. Karl Taube interprets the entire site as an exaltation of sacred war. He says the circles found in the caches are related to the mirrors worn by warriors as well as to the house of mirrors from which the creator serpent originated in the creation story. The bodies found in the offertory caches might be captive warriors. His theory, however, doesn’t explain the significance of the murals.

Aztec water goddess Chalciuhtlicue

Interestingly, the later Aztec water goddess Chalchiuhtilicue, who presides over running water and aids in childbirth, shares many features with the figure in the Teotihuacan murals painted hundreds of years earlier.

New Finds

So back to the amazing new discoveries –

The excavated section of the newly excavated tunnel under the Temple of the Feathered Serpent has 18 walls scattered throughout the length of the tunnel in a zigzag pattern, which archaeologists believe were used to seal off the tunnel on previous occasions. So this same route had been used many times before for some purpose, yet this was the last time. After this offering was placed, the tunnel was purposely filled and sealed.

Gomez feels going down the tunnel and leaving offerings probably had a ritual purpose. The original city was built over a four-chambered lava tube cave. In Mesoamerican cultures, caves were considered portals to the Underworld and the places of emergence at the time of creation. Perhaps, Gomez said, the trip into the tunnel provided the ritual power needed for a new leader. (Photo shows recent discovers in the tunnel, including greenstone figures in the foreground, dozens of conch shells, and plain pottery.

Or the trip into the tunnel could have been a pilgrimage, a way to make contact with powerful spirit forces. Following the pattern evident in so many religious rituals around the world, the supplicant may have offered sacrifices in order to recognize the gods’ power and to seek their help.

A Survey of Discoveries

Back in 1982 and 1989, mass graves were found under and near the same Temple of the Feathered Serpent. The sites, dated to the period the temple was constructed, about 150 AD, included 137 people who’d been sacrificed with their hands tied behind their backs. They were accompanied by cut and engraved shells from the Gulf Coast (150 miles away), obsidian blades, slate disks, mirrors, ear spools, and a greenstone figurine with pyrite eyes. A hundred years later, people left very similar offerings in the tunnel.

In 1999, a burial site was discovered within the Pyramid of the Moon. That site yielded 150 burial offerings, including obsidian blades and points, greenstone figures, pyrite mirrors, conch and other shells, and the remains of eight birds of prey and two jaguars. Again, these are very similar offerings.

The male buried in the tomb under the Pyramid of the Moon was bound and executed, which seems to make it a sacrifice rather than a memorial. All of the human bodies found so far have been sacrificed. Some were decapitated, some had their hearts removed, others were bludgeoned to death. Some wore necklaces of human teeth. Sacred animals were also sacrificed: jaguars, eagles, falcons, owls, even snakes.

The 2014 discoveries, like the others, have been extravagant and gruesome. Some of the precious objects discovered in the tunnel include arrowheads, obsidian, amber, four large greenstone statues, pottery, dozens of conch shells, a wooden box of shells, animal bones and hair, skin, dozens of plain pottery jars, 15,000 seeds, 4,000 wooden objects, rubber balls, pyrite mirrors, crystal spheres, jaguar remains, even clay balls covered in yellow pigment (shown in photo). And some came quite a distance – conch shells from the Gulf of Mexico, jade from Guatemala, rubber balls from Olmec or Maya sites.

Teotihuacan yellow orbs

While this team, like the earlier ones, hopes to find a royal burial, as of this moment, they haven’t. So far, this too seems to be an offertory cache. The difference is that this moment doesn’t mark the building of a new pyramid; it marks the effective end of construction. Some event required this extravagant offering. While some think this cache might be the remains of a huge feast marking a great funerary and sacrificial ceremony, a tunnel 60’ underground seems an odd place for a celebration.

While this team, like the earlier ones, hopes to find a royal burial, as of this moment, they haven’t. So far, this too seems to be an offertory cache. The difference is that this moment doesn’t mark the building of a new pyramid; it marks the effective end of construction. Some event required this extravagant offering. While some think this cache might be the remains of a huge feast marking a great funerary and sacrificial ceremony, a tunnel 60’ underground seems an odd place for a celebration.

The timing suggests the event was more than the death of an old ruler or the ascension of a new ruler who needed the spiritual trappings of leadership. It looks as if the city faced a crisis – perhaps weather changes, disease, internal strife, or some other threat. At this critical point, they might have turned to the Great Goddess, the one responsible for life and death and new life, to help revive the old strength that defined Teotihuacan. Indeed, the murals featuring the Great Goddess as the provider of joyful, abundant life were painted about the same time.

According to Mary Ellen Miller’s book The Art of Mesoamerica, “Constant rain and water crises at Teotihuacan exacerbated the difficulty of building and maintaining the city. The preparation of lime for mortar and stucco requires vast amounts of firewood to burn limestone or seashells, and the more Teotihuacan grew, the more the surrounding forests were depleted. With deforestation came soil erosion, drought, and crop failure. In response, Teotihuacan may have erected ever more temples and finished more paintings thus perpetuating the cycle.”

Whether this environmental degradation from both drought and flood was the crisis that precipitated the offering or only part of it, we don’t know. However, if crops failed, the power structure would soon fail as well.

A Similar Case

In 1200 AD, a terrible drought in what is now Arkansas (USA) drove people to bring their precious stone pipes, engraved shell cups, stone maces, projectile points, and colorful woven tapestries to the site of a new mound to be constructed. They chanted and sang and danced and said prayers after they built high walls and a domed roof around the offering chamber. “They gathered at Spiro,” George Sabo, director of the Arkansas Archaeological Survey said, “brought sacred materials, and arranged them in a very specific way in order to perform a ritual intended to reboot the world.”

Perhaps that’s also what the Teotihuacanos tried to do.*

Article source: MisFitsAndHeroes.wordpress.com/tag/discoveries-at-teotihuacan/