Black Death maps reveal how the plague devastated medieval Britain

Areas of the UK heavily affected by the Black DeathAntiquity/University of Lincoln

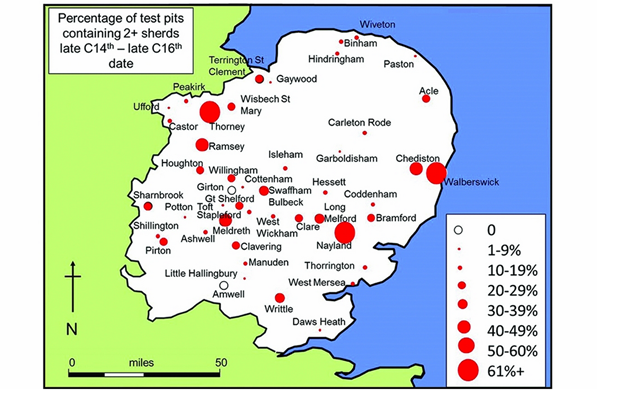

An in-depth analysis of pottery shards has revealed the “eye-watering” impact the Black Death had across rural medieval England.

Towns, villages and hamlets were ravaged by the peak of the plague between 1346 and 1351, and between 75 and 200 million people are said to have been killed across Europe and Asia during several centuries of the disease.

Now a series of maps has been released which reveal the “devastating” and “eye-watering” effect the disease had across the UK as populations fell.

The research was led by Professor Carenza Lewis from the University of Lincoln.

“The true scale of devastation wrought by the Black Death during the ‘calamitous’ fourteenth century has been a topic of much debate among historians and archaeologists,” said Lewis. “Recent studies have led to mortality estimates being revised upwards, but the discussion remains hampered by a lack of consistent and scalable population data for the period.”

“This new research offers a novel solution to that evidential challenge, using finds of pottery – a highly durable indicator of human presence.”

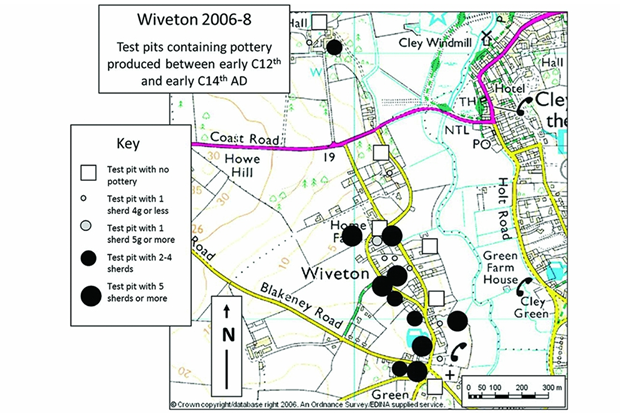

Lewis used pottery shards, gathered from more 2,000 excavated pits

between 2005 and 2014, as a “proxy for the presence of human populations”, showing how a drop-off in pottery finds correlated with the plague epidemic.

Pottery shards are considered to be a good indicator of population levels and comparing amount of shards found in any given test pit can provide an illustration of how many people were living in a particular area.

“Pottery was extensively used in eastern England in the study period,” explained Lewis. “Medieval ceramic vessels were easily broken and difficult to mend, and therefore frequently discarded.”

Maps also show the areas most affected by the Black Death – including Norwich, Cambridgeshire and Hertfordshire – in which declines in population “exceeded 70 percent”. Overall, 55 settlements were studied, with medieval settlements that had since been abandoned not included in the research.

The decline in pottery shards found between the early 12th century and late 16th century was 45 percent.

“This supports the emerging consensus that the population of England remained somewhere between 35 and 55 percent below its pre-Black Death level well into the sixteenth century,” Lewis continued.

“Just as significantly, this new research suggests there is an almost unlimited reservoir of new evidence capable of revealing change in settlement and demography still surviving beneath today’s rural parishes, towns and villages – anyone could excavate, anywhere in the UK, Europe or even beyond, and discover how their community fared in the aftermath of the Black Death.”

But the Black Death isn’t just a thing of the past, Lewis said, pointing to studies that show the plague is still “endemic in parts of today’s world”, and the social upheavals Europe faced after the medieval epidemic.

“It’s sobering to consider that the sustained post-Black Death demographic collapse and stagnation followed pandemics of plague,” she wrote. “The disease is still endemic in parts of today’s world, and could once again become a major killer should resistance to the antibiotics now used to treat it spread amongst tomorrow’s bacteriological descendants of the 14th century plague.”

“We have been warned.”

*Source: Wired UK

Witten by: Emily Reynolds