Arthur Posnansky – The Half-Forgotten Pioneer of Andean Archaeology

The Controversial Legacy of Arthur Posnansky, The Half-Forgotten Pioneer of Andean Archaeology.

By Dave Truman

Arthur Posnansky enjoys a rather ambiguous status in contemporary Bolivian archaeology. On the one hand, he is hailed as the father of the South American nation’s archaeological pedagogy. On the other, many of his findings are ignored and his theories dismissed. There are cultural reasons for this curious ambiguity. Although Posnansky was born in Austria, he spent most of his life in Bolivia studying the remains of Tiwanaku (Tiahuanaco) and the surrounding Altiplano of the High Andes. For this reason, he is almost universally held in high esteem by present-day Bolivians. The implications of what he found, however – after over fifty years of excavations and analysis – do not sit easily with the current archaeological consensus concerning Andean pre-history.

The essential difference between that consensus and Posnanky’s work centers on when Tiwanaku rose to prominence as a sophisticated culture. Contemporary archaeologists consider Tiwanaku to have flourished some time after 1,500 BC until around 500 AD. In doing so, they have drawn almost exclusively on two methodologies: radio carbon 14 dating and obsidian hydration dating. Posnansky dated Tiwanaku to around 15,000 BC by measuring the astronomical correlation of one of the site’s temples. However, he had found much to corroborate this early date in geological evidence and from the numerous physical excavations he had undertaken. Most of this work is simply ignored today because it raises awkward questions about whether these methods should used as the sole arbiters of the age of a given site. This is especially so in the Andes, where the prevailing geological and climactic conditions raise questions about their limitations.

Geology versus archaeology

In fact, geological studies conducted on the Altiplano in the 1980s are far closer to Posnansky’s dating than the archaeological consensus, indicating a human presence of around eleven thousand years. Human occupation there followed the initial shrinking of a great lake, called Tauca, which was formed at the end of the transitions from the Pleistocene to the present Holocene era. These early occupants were hunter-gatherers, by which it is often inferred that they were the “primitive” predecessors of the people who built Tiwanaku. We have, however, no hard evidence of this and their hunter-gathering lifestyle may equally have resulted from the aftermath of catastrophe as much as any innate “primal” qualities they may have had.

Posnanky’s own geological studies indicated that there had been two principal periods of flooding on the altiplano. One was largely of salt water, whilst the other had consisted of fresh. He concluded that the source of the salt water had been the Pacific, whereas the fresh water had originated from melting glaciers. He hypothesised that sea water had become trapped on the altiplano when the Andes had risen rapidly duirng the Pleistocene. Posnansky was not, of course, aware of more recent evidence indicating a sequence of catastrophic changes that had engendered the Younger Dryas. His careful observations of Andean geology, however, were remarkably prescient of those of geologists later in the 20th century, who had started to call into question the exclusivity of uniformatarianism to describe the way that the Andes had formed.

Excavations in Pleistocene strata

Posnansky’s most intriguing findings were from the excavations he made on the altiplano at Tiwanaku and on the shores of present-day Lake Titikaka. Although he was an engineer by profession, he was one of the first to have excavated Tiwanaku systematically. He makes several references in his Tihuanacu, Cradle of American Man, to how previous excavators and treasure hunters had destroyed so much valuable evidence. In the altiplano’s alluvial mud, Posnansky discovered, mixed up with human bones, the remains of species of fish and aquatic fauna that are still living today in Titikaka’s waters. This he took to be definitive proof that Tiwanaku had been flooded at least once in its long history.

Rebuilt wall of Kalasasaya

When Posnansky excavated beneath Tiwanaku’s Akapana Pyramid, he found a strange-looking skull, along with fragments of a human skeleton. He described the skull as being “fosilised,” “deformed.” and of great antiquity. This was because it was discovered deep beneath the Pyramid. He identified its geological stratum as being the same as one in which a toxodon’s skull had been found. Toxodons had lived in South America until the final warming that had marked the end of the Younger Dryas, between about 9,500 BC and 9,000 BC. Current evidence indicates that toxodons preferred drier environments, suggesting that the stratum in question may have dated from earlier than very end of the Pleistocene.

Relief carvings of mega-fauna?

Posnansky identified what he thought may have been relief carvings of Pleistocene animals on the walls and many stone gateways of Tiwanaku. He wondered if some of the carvings – now generally considered to be stylized representations of pumas – might actually have depicted memories of a genus of Pleistocene cats called Smilodon, which had preyed on camelids in western South America. In doing so, he posed a question that modern researchers overlook; why do only some of Tiwanaku’s representations of felines display unusually large canine teeth? It is widely accepted that the puma played a central role in shamanism at Tiwanaku, so the answer to this question may be ethnographic, rather than zoological. Even if the answer, however, is that they are not stylized portrayals of sabre-toothed cats, its investigation would generate a line of inquiry that could enrich our knowledge of this enigmatic site.

The taboo of astronomical dating

If he is remembered at all today, Arthur Posnansky is famous for the polemic that surrounds his astronomical dating of Tiwanaku at 15,000 BC. It is not just that this date is far too early to fit the conventional paradigm, but it implies the possession of a sophisticated understanding of the heavens amongst those who constructed Tiwanaku. This challenges many current assumptions about the intellectual and technological capabilities of the Pleistocene inhabitants of the Andes. Above all, Posnansky employed a methodology of astronomical dating pioneered by Sir Norman Lockyer that is still viewed with suspicion in some quarters.

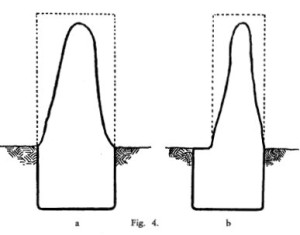

Lockyer’s method measured the angle of the sun’s azimuth on significant dates at sites in Egypt and Greece and then calculated the age of their construction by reference to changes in the Earth’s axial tilt over time. Posnansky used the same basic methodology, measuring the deviation in the position of the eastern cornerstones of Tiwanaku’s Kalasasaya Temple from the azimuth of solstice sunrises in his own time. The resultant date of 15,000 BC raised such furor among some archaeologists that a team of astronomers was dispatched from Germany to Bolivia. They worked for three months to re-calculate the date. In the end, they dated the site at 9,300 BC. Posnansky’s critics persisted in urging them to reduce the site’s age still further, which they refused to do.

Subsequent astronomical dating undertaken by Professor Neil Steede, yielding a date of 10,000 BC, was confirmed by Doctor Oswaldo Rivera in 1996. These dating exercises have benefited from the use of accurate computerized data, especially the Astronomical Alamanac. This gives much more reliable values for the changes in the Earth’s axial tilt over time than Lockyer or Posnansky ever had. Dr Rivera’s work measured the deviation of the angles of solstitial sunrises and sunsets. He did this by taking measurements from all four of the Kalasasaya’s corner megaliths, This rendered it extremely improbable that the differences between the contemporary solstitial azimuths and the positioning of the cornerstones were simply inaccuracies on the part of any putative builders in a later epoch. He concluded that all four cornerstones had been positioned accurately somewhere around 10,000 BC. Dr Rivera resigned from his post as Director of the Bolivian National Institute of Archaeology shortly after this announcement.

Subsequent astronomical dating undertaken by Professor Neil Steede, yielding a date of 10,000 BC, was confirmed by Doctor Oswaldo Rivera in 1996. These dating exercises have benefited from the use of accurate computerized data, especially the Astronomical Alamanac. This gives much more reliable values for the changes in the Earth’s axial tilt over time than Lockyer or Posnansky ever had. Dr Rivera’s work measured the deviation of the angles of solstitial sunrises and sunsets. He did this by taking measurements from all four of the Kalasasaya’s corner megaliths, This rendered it extremely improbable that the differences between the contemporary solstitial azimuths and the positioning of the cornerstones were simply inaccuracies on the part of any putative builders in a later epoch. He concluded that all four cornerstones had been positioned accurately somewhere around 10,000 BC. Dr Rivera resigned from his post as Director of the Bolivian National Institute of Archaeology shortly after this announcement.

The value and limitations of different dating methods

There is a natural tendency for people to select evidence that supports their world-view and ignore any that may question it. In Andean archaeology, it seems that radio C14 and obsidian hydration

dating have been seized upon in order to support the relatively late emergence of civic society. Recent findings – using those same dating methods – have now demonstrated the existence of sophisticated urban life on Peru’s coast at 2,600 BC and in the Andes from at least 3,500 BC. The elevation, climate changes and geological history of the altiplano are capable of producing conditions that accentuate limitations in these dating methods. This has been coupled with a failure to define precisely what is being measured, Neither method can tell us when a stone was worked or set in place, even if it may tell us the last time someone lit a fire nearby, or when a blade was discarded there.

Posnansky’s approach to his life’s work was what we may call today multidisciplinary, but it was not that of a dabbling amateur. He embraced many different sources of evidence and investigated them rigorously. If some of Posnanky’s conclusions and hypotheses are found to be mistaken, they are still worthy of our attention. Even if they do not provide definitive answers, they may at least allow us to ask more pertinent questions about what sorts of people inhabited the Andes at the end of the Pleistocene.

References:

1 Buero Rojo, Hugo, Buero Rojo, Sonia, El Imperio del Sol: Titicaca, El Lago Sagrado de los Incas,

Tiwanaku, Cusco, Machupicchu, Editorial Hispania, La Paz, 1987, p101.

2 El Imperio del Sol, p87.

3 Posnanasky, Arthur, Tiahuanacu, La Cuna del Hombre Americano, Augustin, Publ., New York and

Minister of Education, La Paz, Bolivia, p23, Archivo y Biblioteca Nacionales de Bolivia,

http://200.87.17.235/bvic/Captura/upload/TI_T- I-P12345.pdf

4 Tiahuanacu, La Cuna del Hombre Americano, p17.

5 Allan, D.S, and Delair J. B, When the Earth Nearly Died: Compelling Evidence of a Catastrophic

World Change 9,500 B.C, Gateway Books, Bath, England, 1995, p30, citing the work of Zeil (1979).

6 Tiahuanacu, La Cuna del Hombre Americano, pp38-39.

7 Tiahuanacu, La Cuna del Hombre Americano, p44.

8 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxodon

9 Tiahuanacu, La Cuna del Hombre Americano, pp113-115.

10 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smilodon

11 See: Michell, John, A Little History of Astro-archaeology: Stages in the Transformation of a Heresy,

Thames and Hudson, London, 1977, p19,

12 Wilson, Colin, Atlantis and the Kingdom of the Neanderthals, Bear and Company, Rochester

Vermont, 2006, p60. Also: The Flood: A Quest for Atlantis,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5XD7Rm1099Y

13 Atlantis and the Kingdom of the Neanderthals, p61.

14 Hancock, Graham, Faiia, Santha, Heaven’s Mirror, Michael Joseph Publishing, London, 1998,

pp305-306.

16 See: http://www.redhistoria.com/descubren-una- civilizacion-de- 5500-anos- en-peru/#.Vm4TK4TWQyr