Archaeologist identifies long-lost grave of Attalid rulers in Turkey

The monumental burial site at Yiğma Tepe, atop a hill by Pergamon, had to have been created to commemorate somebody vastly important. Prof. Felix Pirson thinks it was the Attalid rulers. DAI-Pergamongrabung – A. Weiser

Monumental burial site had been known for 200 years but new evidence indicates it housed bodies of kingly importance

The long-lost burial site of the Attalid Dynasty, which ruled the city of Pergamon after Alexander the Great, may have been identified. A vast mound first excavated almost 200 years ago in western Turkey is the spot, Prof. Felix Pirson thinks – and hopes to prove it soon using advanced technologies.

Certainly, the monumental burial site at Yiğma Tepe, atop a hill by Pergamon (today Bergama) had to have been created to commemorate somebody vastly important.

“What points to the Attalids is the monumental size and indications for dating in the 2nd century BCE,” Pirson, director of the Pergamon excavation projects, told Haaretz.

Beyond its sheer dimensions, the architecture and the alignment of the tomb, to the western side of the Temple of Athena and stairway side of the Great Altar, also support the theory that it was the tomb of a great Attalid ruler, Pirson says.

Royal palaces, but where are the kings?

The Hellenistic kings of Pergamon ruled over most of minor Asia during 2nd century BCE. The gorgeous Attalid royal capital, deliberately built with extravagant aesthetics to awe, was the embodiment of the kingdom’s wealth and power.

Pergamon began as a fortress atop an isolated hill between two rivers. Pliny the Elder even credits the city with inventing the use of leather as parchment, after jealous Ptolemaic rulers banned the export of papyrus to Pergamon because they feared the royal library, built by King Eumenes II (who ruled between 197-159 BCE), was about to surpass their own in Alexandria. The city lasted into the Byzantine era: on the north slope of the hill, archaeologists have found spearheads, coins and ceramics from that time.

The west slope of ancient Pergamon DAI-Pergamongrabung – A. Weiser

Though Pergamon evolved into a capital of the Attalid kingdom, crowned with temples and sanctuaries, royal palaces and the Great Altar, the burial place of the Attalid kings remained unknown.

All along, however, the burial mounds at the foot of the mountain were a strong possibility.

Yiğma Tepe, which is 158 meters in diameter and 31 meters high, and dominates the Kaikos plain to the south of Pergamon the burial mound was investigated by the early archaeologist Alexander Conze in 1878 – then, the site was at the edge of the modern town of Bergama.

The excavators found that the mound was contained by a peripheral wall (krepis) built of big andesite blocks, but no entrance way to the interior was found in this platform from where the superstructure once rose. Despite intensive digging, which left behind the deep groove in the mound, they never found the burial chamber.

Pirson is hopeful that this season’s investigation, with geophysical and seismic prospection, will bring new information about the inner structure and the building process of this monumental tumulus.

< Spearheads, a ring and other artifacts from the Byzantine age, found at Pergamon. DAI Pergamongrabung

Another magnificent burial that has been excavated sits on the saddle of the İliyas Tepe (St. Elias Hill), to the east of the acropolis mountain. It belonged to an unknown man of grand stature. A tunnel built of ashlar blocks lead to a 2,200-year-old barrel-vault chamber, sealed off by a double-winged stone door that was equipped with a complex locking mechanism of bronze. Neither the massive stone doors nor the locking device was enough to stop grave robbers from stripping the tomb of its treasures.

The looters did leave left behind the skeletal remains of a man, aged 60-75, inside a sarcophagus. Thanks to an unguentarium found in the sarcophagus, a bottle frequently found in Hellenistic and Roman sites, the man’s funerary monument could be dated to the second half of the 3rd century BCE, to the reign of Attalos (241-197 BCE).

The archaeologists believe the deceased was part of the Attalos family’s most inner circle, perhaps a general.

Dörpfeld had also found two other burial mounds on the Kaikos plain, from an earlier era. These two burials, which had been left undisturbed by thieves, are also of the tumulus type, about 30 meters in diameter and date to the mid-3rd century BCE, the era of Eumenes I (who ruled from 263-241 BCE). Each contained a single sarcophagus, and one contained particularly rich “grave goods” – including a golden oak-leaf wreath with Herakles knot (that rested on the deceased’s head), a Nike pendant, two heads of Molosser dogs made of gold, iron weapons, and a coin bearing the image of Alexander the Great. Next to it was another coin, “Charon’s obol”– a coin that was placed with the dead as a fare for the journey to the underworld.

Who had been buried there however is anybody’s guess but the burial custom displays links with Macedonia.

Giants battle the gods

Despite the loss of many of its treasures, the archeological site of Pergamon is one of the finest remaining from the ancient Greek world. Among the most renowned: the Pergamon altar, which is on display at the Pergamon museum in Berlin. Eumenes II built the original to mark his victory over the Gauls. Originally standing on a terrace overlooking the city, it was decorated with a sculptural frieze illustrating the Gigantomachy, a mythic battle of gods and giants.

The biggest revelation of the recent excavations at Pergamon is how the royal capital developedand expanded across the plain from Hellenistic into Byzantine times, and how the Attalids utilized aesthetics in architecture to manifest their sovereign power.

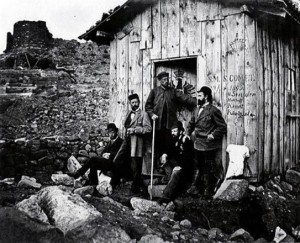

First generation of excavators at Pergamon leaning against the dig barrack – 1879. DAI-Pergamongrabung

“The Attalid rulers, who were famous for their cultural politics at their capital and beyond, recognized the power of aesthetics and messages conveyed by art and architecture to impress both their subjects, strangers and even their enemies,” Pirson told Haaretz.

‘The world as a stage’

To his mind, Pirson explains, the urban layout of Hellenistic Pergamon, i.e. the position of building-terraces and the structure of the street-system, reflects not only practical necessities but aesthetic criteria – and consideration of the surrounding topography to maximize the impression of magnificence.

Even the street system and roads seem to have contributed to the overall aesthetic, being laid out to highlight the spectacular topography of the city-hill by dynamic axes, which were linked in turn to important buildings. This isn’t just theory: the ancient Greeks even had a word for this new spatio-visual technology, skēnographia – a word originating in Greek theater, where the world became the stage.

In short, the Attalids knew how visual media could be used as agents of domination, seduction, persuasion and deception, and configured the Pergamene urban space to manifest their power.

Vaulted tomb that had been equipped with a complex locking mechanism, Pergamon excavation. DAI-Pergamongrabung

In effect, they transformed the city into a stage, where the politicians were the actors, and the people were the spectators.

The kings of Pergamon – who were interchangeably named either Attalos or Eumenes – did not settle for beautifying their own cities. They were also great artistic patrons of the ancient world and showed particular benevolence toward Athens, where the ancient marketplace was beautified by a magnificent reconstruction of Attalos’ Stoa (today housing the finds of the American archaeological school).

Where Satan lives

Not everybody felt awe of the architectural Attalids. Apostle John referred to Pergamon as the city “where Satan is dwelling”. As the meeting place of religious traditions from Anatolia, Greece and the Orient, the place was crawling with cults.

Excavations on the northern side of the hill found rock sanctuaries dedicated to the cults of Meter-Cybele and Dionysus. Even the steepest slopes housed small terraces with sanctuaries.

<Atop Pergamon´s city-hill: The Trajanum with temple terrace. The Attalids were masters of creating awe through aesthetics in architecture. DAI-Pergamongrabung

We know that cult and religion were part of the overall architectural aesthetic, and were an element in city planning because of the existence of a “street-sanctuary” discovered a main street of the city.

Next to a prominent rock formation, a niche, an altar and a tree was situated, enabling the devout to rest in the shade while praying. Until now, such “street-sanctuaries” had only been known from reliefs of the late Hellenistic period.

Written sources speak of Pergamon’s religious diversity. It is the place where the Chaldean Magi (astrologers) are said to have fled from Babylon . Sick people from all over Asia flocked to Pergamon because of its temple to Asclepius, the god of healing and medicine.

“Religious intolerance in the modern sense did not exist in antiquity,” Pirson explains. “As long as the dominant political order and the associated religious system were accepted, other cults and beliefs could be practiced as well. This was a fertile soil for a multi-religious life in the Roman Imperial Age. But it did not spare Pergamon from violent persecutions of Christians in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD,” he said. And, eventually, the millennia-long history of this magnificent city came to an end.*

Clay jars found in the Pergamon excavations. DAI-Pergamongrabung

A cave sanctuary on the hillside of ancient Pergamon. DAI-Pergamongrabung

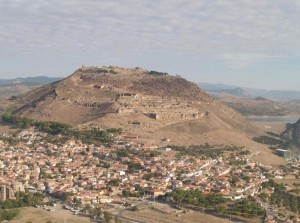

Ancient Pergamon and the modern Turkish city of Bergama: The view from the south. DAI-Pergamongrabung – A. Weiser

South-east curtain wall in the Hellenistic fortification circuit. DAI-Pergamongrabung

Article Credit: Philippe Bohstrom – Contributor Source: Haaretz.com